Author Q&A

BETWEEN FACT AND FICTION

Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart, or in the head?

How begot, how nourished?

Reply, reply.

It is engendered in the eyes,

With gazing fed, and fancy dies

In the cradle, where it lies.

Let us all ring fancy’s knell.

I’ll begin it–Ding dong bell.

–William Shakespeare,

The Merchant of Venice

So sing Portia’s musicians, at Belmont, her vast domain, while Bassanio ponders which casket he must open–gold, silver, or lead–if he is to win Portia’s hand and fortune. Their questions are not unlike those that readers ask of novelists about their novels: How did the idea of writing your book occur to you? How much of it is based on your life? Matters of Honor has provoked its fair share of them, most frequently put to me after readings I have given from that book. I rejoice in contacts with my readers, so I have answered them extemporaneously with results that have seemed to me uneven. This is my first attempt to provide a coherent response.

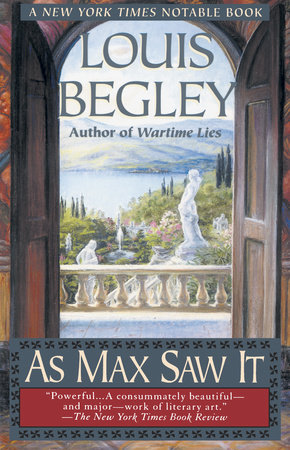

Some time after I had published my first novel, Wartime Lies, my wife, Anka Muhlstein, who is a French historian and biographer, suggested that I should consider writing about how I had set about becoming an American after I arrived in the United States from Poland in March 1947, at the age of thirteen. I replied that I liked her idea, and was already working on it. I was referring to my second novel, The Man Who Was Late, the protagonist of which is Ben, a brilliantly successful and tormented young man, Jewish like me, who after surviving the war in an unnamed Central European country streaks like a comet through the firmament of Harvard College, the Marine Corps, and Wall Street only to crash disastrously in consequence of an unhappy and impossible love affair. That novel, of which I am inordinately fond, could have been the sort of book my wife had in mind, but I had become too engrossed by the destructive relationship between Ben and the woman he loves, and too obsessed by aesthetic concerns–the need I felt for the action of that novel to proceed at a gallop–to pay sufficient attention to the great theme of Americanization. I suppose that I thought, correctly as it turned out, that I would one day turn to it.

An opportunity presented itself in the period that followed the completion of my seventh novel, Shipwreck. My mother’s health had been declining steeply; in fact, she would die soon afterward. I couldn’t avoid thinking intensively about the past, not only the wartime years in Poland but also the years that followed my family’s and my arrival sixty years ago in New York City; Harvard College, which I entered in 1950; army service from 1954 to 1956; Harvard Law School; and the slow resolution of many internal conflicts tearing at me that had their roots in my early youth. As I immersed myself in those memories I began to see that my efforts to become an American had been only one facet of a larger experience that I had shared with others. I was thinking in particular of the man who was my Harvard College roommate from our freshman year until graduation, whose background, ambitions, and destiny were totally different from mine, as well as of other students who had been close friends. We had all embarked on the great adventure of self-reinvention, of remaking ourselves as nearly as such a thing was possible in the likeness of the secret or not-so-secret imago we had chosen. My own reinvention was complicated by the anti-Semitism that was then prevalent in the United States, and the impression I had that normal Americans couldn’t comprehend my experiences during the war and weren’t especially interested in hearing about them.

These assertions may sound strange in the first decade of the twenty-first century, but I am speaking of a time–end of the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s–when the word “Holocaust” had not yet been applied to the slaughter of European Jews, and it wasn’t clear that Auschwitz, Treblinka, Majdanek, and the other furnaces of Moloch were a fit subject for polite conversation.

Thus I came gradually to the decision that the novel about Americanization my wife had “commissioned” and I had in mind would need a wider focus. That a young man whose origins were like mine–Henry White in Matters of Honor–would be at the center of the stage could be taken for granted; I wanted also a personage not unlike my roommate during the four years at Harvard College. He became Archibald P. Palmer III, or Archie, as he wished to be called. I could see fairly distinctly the trajectories of those two young men, including the rather surprising dénouement of Henry’s career. But I didn’t know how the story should be told. When I first tried to write it in the first person, from the point of view of Henry, the result dismayed me. What I had set down was flat and lifeless. I wondered whether I shouldn’t abandon Henry and Archie and move on to a different story. Then Sam Standish, the third roommate, came into my life and I realized that he was the inevitable narrator. He gave me the opening to speak of a milieu I know and find amusing: the “good” families in the Berkshires. Ostensibly a WASP with the right name and the right manners, he could provide the distance from Henry’s specific preoccupations that I thought was necessary. At the same time, he would be secretly as much an outsider as Henry. I would accomplish that by making him an adopted son of parents he doesn’t respect and by raising a doubt about his sexual orientation. To top it off, Sam would be a novelist, therefore qualified professionally to tell this complex story in which he is an actor as well as an observer.

My biography is available to all. Every reader is in a position to draw the obvious conclusion, that Henry’s curriculum vitae on the surface corresponds to mine: We were both Jewish children born in Poland in the early 1930s, and during World War II were in great danger of being killed by Germans; both of us came to the United States in the late

1940s, settled in Brooklyn, N.Y., and after a passage at a Brooklyn public high school moved on to Harvard College and Harvard Law School; we served in the U.S. army. After law school, like Henry, I went to work for a first-class New York law firm, and like Henry I had what I might describe, if modesty didn’t prevent it, as a brilliant legal career. But the superficial resemblance stops when Henry and I go to work: Unlike Henry, I was hired by my firm on my merits, and welcomed with open arms; unlike Henry, I did not find that I had reached the apogee of professional success only to look into an abyss. Like Sam, I have become a novelist; Henry didn’t.

There are innumerable other fundamental differences between Henry and me. They include relations with my parents–to whose memory I dedicated Matters of Honor–the women I have loved, and my children and the joy they have brought into my life. If I were to attempt to list them I would probably obscure the essential point, which the reader is invited to take on faith: I am not a character in a novel, and Henry is not me. I invented him–as I have invented everyone else, with the exception of historical figures, in Matters of Honor and in my other works–using materials taken from my life and from the lives of others whom I have known, but all such materials have been deconstructed and reformed by my imagination. Of course, some personages owe more to living models than others. Archie is greatly indebted to my college roommate; I have intimated as much. Henry’s parents resemble my parents, albeit imperfectly. Sam Standish is not modeled on anyone in particular. He is a pure product of my fancy, but I have poured into him a great deal of myself. That infusion was dictated in part by his having become a writer; a similar case is John North, the novelist narrator of my novel Shipwreck who, in that novel, speaks for me on all literary matters. Sam’s parents are almost completely invented, except for one or two indispensable traits. Many years ago I knew in the Berkshires a stoop-shouldered, sexily thin woman whom I had in mind when I wrote about Sam’s mother, while a Texan I knew slightly provided me with the diction of Sam’s father. There are no identifiable models for Sam’s very proper cousin, George Standish, or for the fascinating and dangerous Margot. No doubt I have known people George and Margot resemble in one detail or another, cases in point being the clothes Margot wears and her half lazy and half haughty way of talking through her nose. Harvard College in Matters of Honor is very much like the college I remember. In three instances I refer to real people who were very prominent there at the time: Harry Levin, Renato Poggioli, and Bob Chapman, each of them an admired member of the faculty. There is no single model for the odious Belgian magnate, Hubert de Sainte-Terre. Like his billionaire colleague, Mike Mansour, who prowls the pages of my Schmidt Delivered, he was derived from several hugely rich men I have known. However, unlike Mansour and Sainte-Terre, none of those men was any good at business. The most striking characteristics that those real-life moguls share with my characters are their egotism, conceit, and frivolity. I am especially proud of the moment when Sainte-Terre reveals the consequence of thumbing his figurative nose at the French government that has really gotten to him: He won’t be promoted to the next higher grade in the Légion d’honneur! This mishap is 100 percent invented and yet I believe that it is also 100 percent accurate. Each of the moguls I have known would have found it to be the unkindest cut of them all.

So this is how fancy is bred and nourished. I could carry the investigation of the real-life content of my novel further, and it is safe to say that every detail in my descriptions, every personality trait of my characters has some real-life antecedent. The question I have to put to myself, however, is whether research of this sort, amusing for me because it is so much like gossip about acquaintances and friends I haven’t seen for a long time, is of any value to the reader. The truth it reveals, that I am present in my novel, should be obvious without it. How could it be otherwise? As Franz Kafka put it to his fiancée, Felice Bauer, urging her half seriously not to be jealous of his characters, the creation of whom he devoted so much of his time, “the novel is me, the stories are me. . . .”