Author Q&A

A CONVERSATION WITH LOIS LOWRY ABOUT THE SILENT BOY

Q. The Silent Boy has an unexpected and startling ending. Did you write the story with the ending in mind?

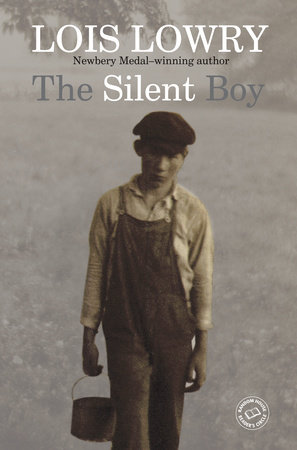

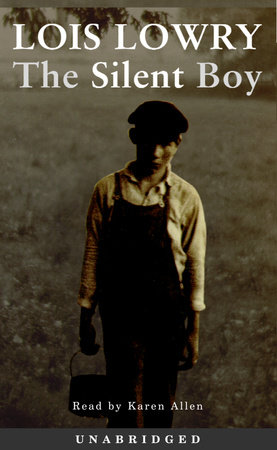

A. I wasn’t certain how The Silent Boy would end when I began writing it. But I did know that the boy Jacob . . . the “silent” boy . . . would have experienced something profoundly disturbing. I knew that because of the photograph, the one on the book jacket, which was the starting point of the novel. It was a real photograph taken by my grandmother’s sister in–I think–1911, but I knew nothing about the boy. Yet looking at his face led me to believe that he was a damaged boy who had experienced some trauma . . . and was perhaps blamed for something . . . for which he was not truly responsible.

Q. As an old woman, Katy looks back on this story as a defining moment in her childhood. Do you think every child has a moment or experience like this that changes his or her life? Were you thinking of any such moment in your own childhood when you decided to write this story?

A. I suppose all humans experience defining moments both in childhood and later. But it is only those who are introspective who recognize and remember those moments. I was a very introspective young person and I can look back on a number of moments in my life . . . including my childhood . . . when a particular set of circumstances changed my way of looking at things. (One such moment is the topic of a short story called “Empress” that was published quite recently in an anthology called Open Your Eyes.)

But I wasn’t thinking of my own defining moments when I wrote The Silent Boy. I was writing fiction, and in fiction one tries to create those pivotal scenes; moments in which characters undergo a change are what an author works toward as a plot progresses.

Q. In the prologue, Katy explains that in a way she is writing this story for her grandchildren, to answer their questions. One also senses that she is writing the story as a way of dealing with her past, as a kind of therapy. Why do you write?

A. I think it is quite clear that Katy, now an old woman, feels a need to tell a story that has haunted her. It was true for me when I wrote my very first book, A Summer to Die, the story of my sister’s death years before . . . one I had told to myself so often. Another book of mine, Autumn Street, does the same thing: the retelling of a childhood tragedy, as a way of explaining it. That is what Katy is doing in The Silent Boy.

I suppose people whose talents reside in art, say, or music, might do the same thing. Mahler, for example, did it when he wrote Kindertotenlieder . . . “Songs on the Death of Children.” But my skill lies with words, and stories, and it is through the genre of literature that I find ways to explore my own life’s events.

Q. Do you prefer writing for children and teens? Have you written any books for adults?

A. I’ve done both, and like doing both. But I sense that writing for young people is the more important work. Literature for young people affects them in profound ways, and at a time when they are still accessible to change.

Q. Where did you find the photographs in the book?

A. Several of the photographs in The Silent Boy–including the jacket photograph–came from the collection of Mary Fulton Boyd Wood, who was my great-aunt and who was a photographer in the early 1900s. I started the novel from the photographs I inherited from her. Then, when I decided I wanted an old photo to open each chapter, I had to find others. I got them from friends and from a New Hampshire antique shop. The photograph near the end, of Paul and his mother, he in uniform, was a particularly lucky find, I think . . . their expressions and postures say so much.

Q. You write in many genres–how does writing historical fiction differ from writing science fiction, and from writing fiction set in contemporary times?

A. Of course the difference lies in the research and in the struggle for accuracy of details. You get to make that stuff up, in most fiction! But when you deal with actual historic events, as I did in Number the Stars, or in historic times, as in The Silent Boy, you need to place things specifically. The research is fun, actually. I only wish my mother . . . who was born in 1906 . . . had still been alive when I wrote The Silent Boy, because she could have told me so much about clothing, games, furniture, all those things. As it was, I found a lot of details in an early Sears catalogue! But it wasn’t as firsthand as it would have been from my mom.

Q. Why did you decide to write this story from the perspective of Katy as opposed to the viewpoint of Jacob himself? When you want to tell a story, how do you choose from whose point of view you’d like to tell it?

A. Jacob is without a voice, really. So I looked for the right “voice” to tell his story and remembered that my own mother was a child then. I dug out old photographs of her, and she became Katy (my mother’s real name, incidentally). That decision provided a wonderful challenge for me as a writer because it meant I would be using an unreliable narrator . . . that is, a child who is too young to fully understand the events she is describing, but who is articulate enough to describe them.

I like writing either in the first-person or the limited-third-person point of view. Somehow each story chooses its own narrative viewpoint.

Q. It seems you often write about a child who is isolated from the world by a special gift or special knowledge (as in the The Giver). Jacob is also isolated from the world by a difference in mind. What drives you to tell these stories?

A. The most interesting protagonist for a novel is always an intelligent, observant, and articulate person . . . whatever the age. Jacob is not really the protagonist of The Silent Boy, though the story is about him. It is Katy, the narrator, who has the keenness of understanding and recollection to tell his story. . . . Of course it becomes her story as well.

But it is true that Jacob is the outsider in this book. Those who are set apart for some reason are always fascinating characters for a writer to explore.