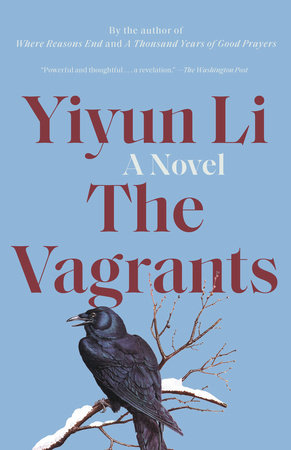

The Vagrants

By Yiyun Li

By Yiyun Li

By Yiyun Li

By Yiyun Li

Category: Literary Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction

-

$20.00

Feb 16, 2010 | ISBN 9780812973341

-

Feb 03, 2009 | ISBN 9781588367730

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Crossing the Mangrove

Through the Ivory Gate

The Year of the Runaways

Before, During, After

All Souls

Divisadero

Segu

Reunion

Two She-Bears

Praise

“Yiyun Li has written a book that is as important politically as it is artistically. The Vagrants is an enormous achievement.”—Ann Patchett, author of Run

“Every once in a while a voice and a subject are so perfectly matched that it seems as if this writer must have been born to write this book. The China that Yiyun Li shows us is one most Americans haven’t seen, but her tender and devastating vision of the ways human beings love and betray one another would be recognizable to a citizen of any nation on earth.”—Nell Freudenberger, author of The Dissident

“This is a book of loss and pain and fear that manages to include such unexpected tenderness and grace notes that, just as one can bear it no longer, one cannot put it down. This is not an easy read, only a necessary and deeply moving one.”—Amy Bloom, author of Away

“A starkly moving portrayal of China in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, this book weaves together the stories of a vivid group of characters all struggling to find a home in their own country. Yiyun Li writes with a quiet, steady force, at once stoic and heartbreaking.”—Peter Ho Davies, author of The Welsh Girl

“There is a magnetic small-town universality to The Vagrants…but this is small-town universality with a difference. That difference is Communist China. The town isn’t small; it only feels that way, as a provincial city where everyone seems to know his neighbor’s business.”—Janet Maslin, The New York Times

“Yiyun Li’s extraordinary debut novel [is] beautifully paced, exquisitely detailed. . . . An amazing technical achievement… . . . Li’s genius lies in her ability to blend fact with an endlessly imaginative sense of the interplay of forces that powered the massive shift in the social order that led to Tiananmen Square. . . . In this most amazing first novel, Yiyun Li has found a way to combine the jeweled precision of her short-story-writer’s gaze with a spellbinding vision of the power of the human spirit.”—Chicago Tribune

“She bridges our world to the Chinese world with a mind that is incredibly supple and subtle.”—W Magazine

“A Balzacian look at one community’s suppressed loves and betrayals.”—Vogue

“A sweeping novel of struggle, survival, and love in the time of oppression. . . . [an] illuminating, morally complex, and symphonic novel.”—O Magazine

“Magnificent.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Li has poured her prodigious talent into The Vagrants. . . . Familiarity with Chinese history isn’t at all necessary to relate to the grief, pain, confusion, fear, loyalty, suspicion, and love portrayed by the characters in this deeply affecting story. . . . The Vagrants has a confident, democratic style that gives a distinct voice to every character. ‘Growing up in China, you learn you can never trust one person’s words,’ Li says. ‘People’s stories don’t always match.’ But one thing is clear: Li’s stories matter.”—Elle

Awards

American Library Association Notable Books WINNER 2010

IMPAC Dublin Literary Award FINALIST 2011

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In