After World War II, the Allies tried many of the Nazi Germans who had murdered, tortured, and committed other war crimes during the Holocaust. Among those other war crimes was the carrying out of 375,000 forced sterilizations for the purpose of eliminating supposed genetic deficiencies from the German gene pool.

One of the primary arguments that the Nazis raised in their defense was the fact that they had largely lifted those policies from the United States where more than half the state legislatures had passed forced sterilization laws, where states had already carried out tens of thousands of such sterilizations, and where the Supreme Court in a 1927 case called Buck v. Bell said it was perfectly legal to do so.

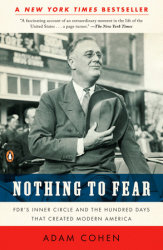

In Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck, author Adam Cohen revisits a surprising and unfortunate period in American history when evolutionary science became social policy and the most respected names in the medical and legal communities gave eugenics encouragement and legitimacy. Penguin Random House sat down with Cohen earlier this week to talk about the book.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: The underlying facts of this are pretty astonishing. How did you get onto the topic?

ADAM COHEN: When I was in law school, I knew about the case and about the famous saying that “three generations of imbeciles is enough.” I went to Harvard where Oliver Wendell Holmes was a major figure. There are portraits of him in the hallways, and people speak very highly of him. So I knew about the case and I knew about Holmes, but I didn’t know too much about it. And when I started digging into it, there was so much I hadn’t known about.

PRH: When did Charles Darwin’s research about evolution start influencing the way people thought about human health, disease, intelligence, etc.?

AC: Darwin’s work was in the mid-1800s in England. It was actually his half-cousin Francis Galton who was the founder of eugenics. He was playing with the idea that Darwin had uncovered that nature was sorting people and leading to survival of the fittest. Galton thought that if we could do what nature was doing, we could do it more methodically and in a more kind way. That started in England and then came over the America in the early 1900s.

PRH: What does eugenics actually refer to?

AC: Eugenics means “good birth.” It’s from the Greek. There were actually two kinds of eugenics. Positive eugenics, which Galton was more inclined toward, encouraged people who had good genes to reproduce and match with people that would result in good offspring. Negative eugenics was actually preventing people who were thought to be unfit from reproducing. That element led to the genetic sterilization movement and about thirty states adopting laws to stop certain people from reproducing.

PRH: In the book, you wrote about the eugenics movement as an effort “to use newly discovered scientific laws of heredity to perfect humanity.” Did that not sound a little creepy to anyone at the time?

AC: You would think there would have been more people to say that, but eugenics was very popular. It was adopted by a lot of thought leaders at the time. The president of Harvard was a eugenicist. There were two major geneticists at Harvard writing in a positive way about eugenics. Medical journals were filled with pro-eugenics sterilization articles. The American Bar Association president endorsed a eugenics law in Connecticut. The thought leaders thought it was a great idea that would lift up humanity.

PRH: Did that give you a pessimistic take on the idea that a wide population will adopt a bad idea?

AC: It did. The book is organized around five characters. There’s Carrie Buck herself, and the other four characters who played big roles represented four revered professions that we would hope would lead society in the right direction. One was a doctor who ran the Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded in Virginia. One was a lawyer who brought the case to the Supreme Court. One was a scientist who was one of the main advocates for eugenics. And one was a judge, Oliver Wendell Holmes.

These are the institutions that you would want to step up and say, “This is wrong, this is bad, and this denies Carrie Buck her rights.” None of them did that. Their professions were similarly in favor of doing what was done to Carrie Buck. Oliver Wendell Holmes says that “three generations of imbeciles is enough,” but the imbeciles turn out to be these four educated people who misunderstood what was going on around them.

PRH: Albert Priddy was the doctor who ordered Carrie Buck sterilized, and that was completely against her will. How did he and the AMA get over the idea of “first do no harm” to do something that actually impaired this patient?

AC: That’s absolutely true, but they didn’t view it that way. People like Dr. Priddy were trying to deal with the medical conditions before them. He was running the Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded. He saw no good way to treat epilepsy, which there was not. He sees feeblemindedness as something he also doesn’t have a way to treat. For him and for other doctors, there was no drug or vaccine but they could remove the genes from the gene pool. In their mind, they thought this was a solution to a medical problem.

PRH: Was their understanding of Darwinian evolutionary theory good science?

AC: Not really. There’s no gene for feeblemindedness. There are all kinds of recessive genes so that someone who appears to be healthy may be a carrier of the gene you’re trying to eliminate. The science and math of it are such that you just wouldn’t be able to get the recessive genes out of the population. We all have things in our family lineage that would be good to get out, but then none of us would ever have children.

PRH: The Immigration Act of 1924 allowed immigration from Western Europe but not from Eastern Europe, which seems today like a weird thing to do. We would look back at that as trying to distinguish among different groups of white people.

AC: That’s right. In 2016, it seems like an Italian or a Jewish person from the Ukraine seems a lot like another Caucasian, but back then there were very big distinctions. Jews and Italians were regarded as very other and not all that white. I was shocked reading the way people spoke in the 1920s — including members of Congress — about Italians and Jews. It was incredibly raw and bigoted. The 1924 Act was also designed to stop Asian immigration to the West Coast.

PRH: How similar is the rhetoric today about immigration to what it was then about the idea that immigrants are harming the economy and changing the culture in the ways we don’t want.

AC: It’s very similar, though back then there was no concept of political correctness. I’m not saying we don’t get extreme statements now, but it was much more raw back then. People like Madison Grant, who was a big eugenist at the time, would write with disgust and horror about seeing Polish Jews in New York City. These were people who went to fancy schools and were on the boards of institutions like the Museum of National History using that kind of rhetoric.

PRH: The book is oriented around this one particular case about Carrie Buck. Who was she?

AC: She was a young, white woman born to a poor family. Her father disappeared early on, and she was raised by her mother without a lot of resources. They lived part of the time on the street. She was taken in by a foster family in Charlottesville, Virginia. She did OK there until a nephew rapes her and she’s pregnant out of wedlock. This was a day and age when that was not acceptable, and the family was possibly worried that the nephew would be prosecuted.

Rather than send her to a home for unwed mothers, they had her declared feebleminded which wasn’t hard to do for a woman pregnant out of wedlock. She was sent to this colony at the time the director was looking for a case to test the new Virginia eugenics law. And that case went to the Supreme Court, which determined Virginia could start sterilizing people.

PRH: Has this case been struck down, or did it just wither away?

AC: You know, it hasn’t been struck down. It really is still good law. It was relied on by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in 2001 in a sterilization case. The Supreme Court had an opportunity to overturn it in 1943 and chose not to. They struck down Oklahoma’s sterilization law on narrower grounds.

PRH: Views on the issue have changed, obviously. Was there a precipitating event or movement that began to change those views?

AC: There were really two. Eugenics was gathering steam after Buck v. Bell in 1927, and the rise of Nazi Germany took a lot of steam out of it. The Nazis were adopting their own eugenic sterilization modeled largely on our program. The more people associated eugenics with this idea of building a master race and anti-Semitism and racism, it came to be seen as un-American. During the 1930s and early ’40s, a lot of the organized eugenics in the United States began to fade. The other was the movement in the 1960s to recognize the rights of marginalized people, including inmates and the mentally ill.

PRH: The part about the Nazis is unsettling. I was going to ask if the Americans and the Nazis were looking at the same evolutionary science, but the Nazis were looking at our evolutionary science.

AC: And they were looking at our statutes. We were a role model for them.

PRH: Were there moments in your research where you just couldn’t believe this was ever the norm in the 20th-century America?

AC: Yeah, there were. As many as 70,000 people were sterilized around the country, which was rather shocking. The other was reading how Oliver Wendell Holmes thought. I had learned about him as this great justice, and the degree to which he was incredibly bigoted and condescending toward people who weren’t of his so-called high birth made him in many ways a terrible judge.