Suzanne Fisher Staples

Photo: © courtesy of the author

“My ideas are sparked by my passions—for the exotic (which I manage to find almost anywhere), for the particular details that make other people’s lives unforgettable.”—Suzanne Fisher Staples

Suzanne Fisher Staples is the award-winning author whose novels for young adults include Haveli, the sequel to Shabanu; Dangerous Skies; and Shiva’s Fire. Before writing books, she worked for many years as a UPI correspondent in Asia, with stints in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I come from a literal family. Everybody says just what they mean, with few embellishments, regardless of who likes it, or whether it makes sense.

“How do you suppose that we ever ended up with a writer in this family?” my mother asks.

“Who knows?” I reply. “Anyway, I may be something else next year.” But it makes me wonder what exactly my family has had to do with my being a writer. Here are some things I remember about growing up among them.

My father and brother are engineers—they can tell you how anything works. When my brother won the Jermyn (Pennsylvania) Soap Box Derby race on the hill outside our house on Franklin Street, I was sure our family had reached its pinnacle of fame.

My mother, who acts and speaks without pretense or subtlety, is matter-of-factly brave and has an intuitive mind. You didn’t dare contemplate doing anything you weren’t supposed to do when she was around. “Don’t you even think about it,” she’d say. When I was twelve, Charlie Fron, our school bus driver, told me she was a good mother, and that she could make a whole busload of kids behave by just looking at them. I stood there a moment, breathing in the silage smell of the bus (Charlie kept it in his barn when the weather was cold) and thought my heart would burst with pride.

My father’s mother, Mema Fisher, was gentle and lovely—she knew about color and texture and mood. Her eye was always cocked for a shapely flower, even if it was a weed; her ear was always tuned to the sounds of the woods. She had a chaotic garden that was always in bloom, and I loved going to her sitting room to listen to our favorite songs (which included “Mockingbird Hill”) on her record player.

Mema Brittain, my other grandmother, and my aunt Elaine were compassionate women. They were capable of understanding and forgiving almost everything. Unlike the rest of my tall, large-boned family, they were delicate and feminine. I was a flower girl at Aunt Elaine’s wedding, and I treasured the weeks of preparation, during which the two of them introduced me to the mysteries of face creams and perfume and silk slips.

I found out much later why it was that my mother had absolutely nothing (except love) in common with the two of them—but that’s another story.

When I was small, I would float in the bathtub made especially for my very long father and create scenes in my head in which I would be a diva or a famous actress.

I lived to fish. In the summer, I got up before dawn and climbed into my bathing suit, shorts, and T-shirt. I’d spend every day on the dock in front of our summerhouse on Chapman Lake with a line in the water, daydreaming about all the exotic places I’d ever heard of, stopping only when it got hot to jump into the icy water. At night we’d go out with flashlights to pounce on nightcrawlers for the next day’s fishing. My sister Karen thought my activities were unspeakable. She and her friends met to paint their nails. (Another story, perhaps.)

I was a liberal arts major in college, mainly because I couldn’t resist the temptation to read to my heart’s content and get credit for it. After graduation I had various jobs, all having something to do with writing and research. Eventually I landed in Hong Kong, where I became a reporter for United Press International. For six years I alternated between being a desk rat and covering the China story, meeting scholars, artists, lawyers, and businessmen who had been inside China, which until 1978 had been closed to Americans for a quarter of a century. I played tennis overlooking the harbor, sailed on the South China Sea, ate Suchow food in the back alleys of the Western District, and sometimes talked until dawn in hotel bars with triad gang members, Chinese Communists, and other questionable characters who would have made my mother’s hair stand on end. (Yet another story!)

When UPI offered me my own bureau in South Asia, my mother said, “Come home. Quit this Mata Hari life and meet a nice man, get married, and have some children.” But I had friends who were living sensible lives, and they hadn’t necessarily ended up with love, marriage, and houses full of happy children. So I went to India.

It’s been said that revolutions happen in ten-year cycles. In 1989, it was the extraordinary events of Eastern Europe. In 1979, the year I went to India, the revolution in Iran resulted in the taking of American hostages. Here are some of the things that happened that year in the countries my UPI bureau covered: In Pakistan, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was hanged. Islamic fundamentalists burned the American Embassy in Islamabad with ninety people inside. Most of them survived, but six people died. In India, Indira Gandhi presided over the demise of the government of Morarji Desai and returned to power, beginning a period of more violence than at any time since the aftermath of the independence of India and Pakistan from British rule in 1947. Civil war broke out in Afghanistan, two prime ministers were killed in office, and Soviet troops entered the country, to remain for ten bloody years.

Keeping up with these events resulted in the most adventurous phase of my life to date. I traveled extensively with Mrs. Gandhi as she campaigned. We talked early in the morning over tea and late at night over warm milk. I shot the first photographs of Soviet troops being airlifted into Kabul. In the ranks of soldiers marching across the tarmac at the Kabul airport, one carried a Christmas tree on his shoulders. Fear was as thick as dust in the air. Our Afghan colleagues and friends began to disappear.

Three years followed in Washington, during which I worked on a part-time basis for The Washington Post and began to write fiction. I returned to Pakistan in 1985 to work under contract to the U.S. Agency for International Development on a study of poor rural women. It was during this time I met an extraordinary girl in the Cholistan Desert, the daughter of a nomadic camel herder, whose story became the basis for Shabanu: Daughter of the Wind and Haveli.

If there is anything special at all about us odd ducks who write, it is our passion for stories. I used to worry that I’d run out of stories, but so far I haven’t. If I ever do, I plan to take up fishing again.

PRAISE

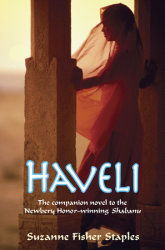

HAVELI

—A Booklist Editors’ Choice

—An ALA Best Book for Young Adults

“Again, Staples imbues Shabanu and her beautiful, repressive world with a splendid reality that transcends the words on the page.”—Starred, Kirkus Reviews

“As freshly inspired as its predecessor.”—The Bulletin

“Page-turning intrigue.”—Starred, Booklist

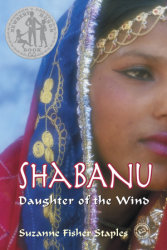

SHABANU

—A Newbery Honor Winner

—An ALA Notable Children’s Book

—An ALA Best Book for Young Adults

—A Library of Congress Children’s Book of the Year

—An IBBY Honor List Book

—A Horn Book Fanfare

—A New York Times Notable Book of the Year

—A Notable Children’s Trade Book in the Field of Social Studies

“One of the most exciting YA books to appear recently. . . . Staples has given readers insight into lives totally different from their own, but emotions resoundingly familiar.”—Starred, The Bulletin

“Shabanu is an unforgettable heroine set like a fine jewel in a wonderfully wrought book.”—Starred, Kirkus Reviews

“Staples has accomplished a small miracle in her touching and powerful story.”—The New York Times

“Remarkable . . . a riveting tour de force.”—The Boston Globe