Oral history is as simple and unvarnished as history gets.

You ask someone questions. You transcribe it. Boom, done. That’s oral history.

The reason they’ve come to occupy a prominent place in the popular culture of late owes partly to that immediacy — the I-was-there first-person-ness of it — but increasingly to the storytelling skill of the journalist (historian? editor?) who conducts the interviews and then sifts through hundreds or even thousands of pages of transcripts to build a story.

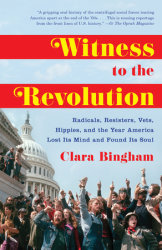

It’s time-consuming, pointillist work. I wrote a 4,400-word oral history of a TV show for Wired that took two months and many rounds of editing to put together, so I can only imagine the work that went into Clara Bingham’s 550-page Witness to the Revolution, an indispensable new oral history of the critical months of social upheaval in 1969 and 1970.

Those were the months when the anti-war movement was at its apex with the Kent State shootings, when the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground employed violence as a tool of racial equality, and when feminists poured into the offices of Ladies Home Journal demanding a female editor in chief. It was a point in American history when you could see the country changing from a (frankly) white-male hegemony to a more multi-cultural society.

We sat down with Bingham to talk about the work that went into Witness to the Revolution, her thoughts on a pivotal moment of social and cultural change, and the new prominence of oral history as a literary form.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: I interviewed Emily Bingham this time last year for Irrepressible, and you both grew up in Louisville. Are you sisters?

CLARA BINGHAM: We’re first cousins. We’re very close. Irrepressible is about our great-aunt.

PRH: Do you talk much to each other about books?

CB: Oh, all the time. Her book came out last June, I had a book party for her, coached her on publicity. Now with my book out, she has a lot of advice for me. She was just in New York for an award from the Lambda Literary Association.

PRH: Witness to the Revolution is an oral history, which is a popular genre right now. Do you think the big crush of oral histories of TV shows, movies, etc., online has re-popularized the form?

CB: Anecdotally, it seems to me that there are a lot of oral histories out there. New York magazine and Vanity Fair do a lot of them. If you look at books, Tom Shales wrote Live from New York about “Saturday Night Live” and Those Guys Have All the Fun about ESPN, which were both very popular oral histories. The Nieman Foundation interviewed me and a lot of other people for a story about oral history being back in vogue.

PRH: Did you know what you wanted the book to be when you started doing interviews, or did you figure it out as you went?

CB: I decided to focus on the 1969-70 school year and researched the events of that year. I decided on the events I wanted to write about, and then I went and looked for the players in those particular events.

PRH: Were most of the people that you wanted to talk to alive and available to talk to?

CB: Most of them were. Some of the people from the 1960s had died — Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, William Kunstler, Leonard Boudin, Howard Zinn — and six people have died since I did the interviews. It felt like a very good time to get this generation to reflect on their lives. If I had waited another five years, it may have been too late.

PRH: Did you feel like the passage of time since 1969/1970 had impaired people’s memories or softened the details?

CB: Oral history immediately after the fact is the best way to do it, so it was riskier to do an oral history this far out from the events. What I found, though, was that these were very traumatic experiences. People who were at Kent State — reporters, people who got shot — did not forget one thing about what happened there. The adrenaline seers your memory. Some people had written memoirs, so I had those to fall back on.

PRH: Oliver Stone was an interesting name to see in the list of people you talked to. What did he tell you?

CB: He was a Vietnam veteran. He was in Vietnam in the infantry in 1969. He enlisted out of Yale and could have been an officer, but he didn’t want to. It was fascinating to hear the story of why he went to Vietnam, what happened there and his difficult experience returning to America. He talked about how he healed himself from the trauma of his wartime experience by making film. He was able to go to NYU film school on the G.I. Bill.

PRH: Jane Fonda was another person you talked to. Was she difficult to wrangle for the interview?

CB: With people like Oliver Stone, Jane Fonda, Daniel Ellsberg, it helped to have people who trusted me that they knew. I was able to get to Jane Fonda through her biographer Patricia Bosworth, who I knew.

PRH: I suspect word spread once you started doing interviews that this was going to be a project where you gave people an opportunity to tell their own stories.

CB: Right, and people were definitely gun-shy about that. The country was very divided then, and a lot of people I interviewed were lightning rods for some of those issues. The fact that this was going to be an oral history helped. I told them I didn’t have an axe to grind and that I was giving them a chance to tell their story in their voice.

PRH: This period that you’re writing about was a time when there were what today we would call domestic terrorist organizations. Did you find much resistance from people who worried that they might be admitting criminal conduct to you?

CB: The members of the Weather Underground were cagey. One person said, “I don’t really like talking about my felonies,” which I thought was a great line.

PRH: A lot of those people you probably knew from Bryan Burrough’s book Days of Rage were either potentially going to talk to you or definitely not going to talk to you.

CB: I was nearly finished with my first draft when Bryan’s book came out, and I was amazed by it. He broke a huge story about the Weather Underground that nobody had ever written. He identified and got a long interview with the chief bombmaker for the Weather Underground, which was fascinating. I was able to talk to a few people who didn’t talk to Bryan including Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers.

PRH: Why were people blowing up buildings?

CB: One of the reasons I wrote this book was that I wanted to know what would motivate someone to do that. What I found were people like Karl Armstrong, who blew up an Army Mathematics Research Center building with three other people in 1970. That was a tragic bombing because it accidentally killed a 33-year old physics researcher who had three children who was working in the building late that night. Armstrong became radicalized. He went to Chicago in 1968 during the Democratic Convention, was brutally beat up by cops and saw other people get beat up. That really changed him. When the My Lai massacre was exposed in November 1969, he was horrified to learn that American soldiers had killed 500 villagers. He felt like he had to do anything he could to end the war.

PRH: Did Seymour Hersh tell you anything interesting about his work uncovering the My Lai Massacre?

CB: Sy Hersh was one of my favorite interviews. The story of how he found Lieutenant William Calley was fascinating. He found out Calley was at a military base in South Carolina off of one tip he got from a source in the Pentagon, and that led to Calley’s lawyer in Salt Lake City, which led him back to Calley. It was a huge, important work of investigative reporting.

PRH: Do you have an overall theory of the 1960s?

CB: It’s hard to do because so much happened in the 1960s, but I might conclude that the New Left, the anti-war left, lost most of its political struggles. They weren’t able to end the war as soon as they wanted to. They weren’t able to rein in capitalism or imperialism or even racism. But they won many cultural battles, and those are the ones that have really lasted and had a profound impact on changing what America is as a country.

PRH: Second-wave feminism, environmentalism.

CB: Exactly. Gay rights, the back-to-the-land movement, rock and roll, the psychedelic revolution. There are so many parts of that cultural revolution that are still with us today and have continued to evolve. It was only a year ago that gay marriage was legalized, and that seems to me like one of the final chapters in the culture wars that began in the 1960s.