In 2001, with fifty dollars to his name and a heavy heart of gold, Wayne Dale Matthysse turned an empty plot of land in Cambodia into a sanctuary of hope. Following the HIV crisis that befell the country in the 1990s, Matthysse created Wat Opot with the aim to help victims of the virus, victims abandoned by family and stigmatized by an unforgiving society.

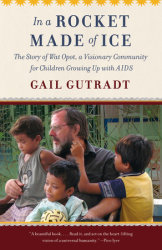

Today, a testament to the thriving life in Wat Opot can be found in journalist Gail Gutradt’s powerful book In a Rocket Made of Ice. With patience, compassion, and an eye for the poetic, Gutradt’s memoir of her time as a volunteer at Wat Opot beautifully captures the heart behind the heavy circumstances that bring the community’s residents together.

Here, Gail reflects on the kinds of things she learned from the children of Wat Opot, and the kind of light her book sheds on Cambodia and AIDS.

EVERYDAY EBOOK: The role of “teacher/caretaker” is two-sided. While you looked after the children of Wat Opot, what do you think the children of Wat Opot helped teach you?

GAIL GUTRADT: I learned from them every day. Sometimes it was catching my own habitual reactions from how I was raised, and becoming conscious that I was judging in a way that I had been judged, and finally becoming conscious enough to pull back from that. Often, a word from Wayne would jolt me out of my reactiveness, as when I complained to him that the Pagoda Boys (village kids who had been troublesome and were sent to live with the monks as a kind of boot camp), were double dipping when I handed out allowances. Wayne said simply, “What would you do if you had nothing at all?”

I was also deeply touched by the children’s compassion for each other. Their understanding was so much deeper than mine. Sure, they are kids and can give each other a hard time. But they have a deep sense of fairness and family. Once, I was taking a photo for Pesei and his sister, whose yei [grandmother] had come to visit. Another little girl kept stepping into the frame, and finally I asked her, “Why do you want to be in the photograph? She’s not your yei.” Pesei put his arm around her and drew her close and said, “But she is our family too.”

I was also awed by how the children took responsibility for their siblings. Some came voluntarily to live at Wat Opot to comfort a younger brother or sister with AIDS, even though they could have stayed at home with grandparents. I never heard anyone complain about that, and as the older ones left for university, they spoke of what they could do to take care of their siblings when they were old enough to venture into the world. One boy brought each of his four siblings to Wayne as they reached school age, so that they might get an education. They are all doing wonderfully.

EE: What are some popular misconceptions about Cambodia that your book helps overturn?

GG: I’m not sure people here think enough about Cambodia to have many misconceptions. It’s not much in the news in this country. But I would guess that their images of the country date back to the Khmer Rouge days, or if they were in the military during the Vietnam War, perhaps it is colored by that experience. Even if they have visited, it’s only to Angkor Wat or maybe Phnom Penh for a day or two. In the book I tried to describe village life, what I could see of it as a visitor, so people could get an idea of how many rural Cambodians live. But I know I only scratched the surface, because there is a rich social and ritual life a visitor is not part of. When I was getting ready to go over the first time, my friends were scared that it might be too primitive, but if you have traveled at all it’s pretty much what you expect. Although Wat Opot is surrounded by villages, we have some definite advantages. Up until a few years ago we only had a generator, and could afford to run it only two hours a night. People in the village sometimes had car batteries they used to power a light or, rarely, a tv. But you know, that was really lovely, just sitting at night looking at the stars without the noise and distraction of street lights and media. I believe we need to value that much more, and I hope that comes across in the book.

Also, people are people, and we all just want to be happy and have a little security in the world, food, shelter, being able to take care of our children. I hope readers see that.

I also hoped to give them a taste of the joy that can accompany even the sorrow of losing a child with AIDS because for a brief time they have been part of a family that loved and cared for them. It is the challenges and how we chose to accept and work with them that give life meaning.

Get more more from our conversation with Gail Gutradt here.