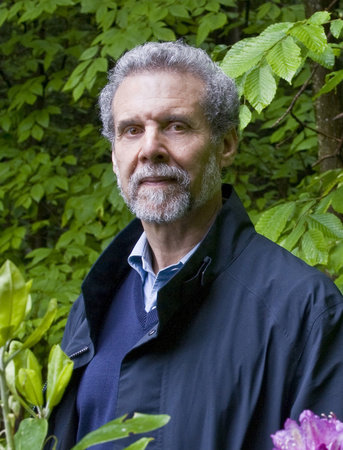

Daniel Goleman is the New York Times bestselling author of the groundbreaking book Emotional Intelligence. A psychologist and science journalist, he reported on brain and behavioral research for The New York Times for many years, and has received several awards for his writing. He is the author of more than a dozen books, the latest of which, written in collaboration with Richard J. Davidson, is Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind, Brain, and Body. Goleman is a founding member of the board of the Mind and Life Institute, a cofounder of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, and codirector of the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations. We recently corresponded with Daniel to address the rise of meditation, what works in the practice of it, and more.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: Many people associate mindfulness and meditation with a particular “type” of person – perhaps someone who skews a little earthier or perhaps more bohemian. Given its surge in popularity, this is clearly not the case. Can you talk a little bit about the moment in time when this shift happened, what took place around the time it became something for everyone?

DANIEL GOLEMAN: I’d guess the last five years or so have seen an immense upsurge in numbers of people meditating, and a similar uptick in the numbers of meditation apps offered, businesses bringing in mindfulness, and schools teaching kids to train their attention better. And now it’s not some exotic endeavor, but, like yoga, something for everyone.

PRH: Is there anyone for whom mindfulness really won’t work? Any particular personality type?

DG: The only real indicator of whether mindfulness will work is how motivated you are. If there’s no interest, there’s no hope.

PRH: Your own history in mindfulness goes back decades, and you’ve had years of in-depth study and research and practice. From your own extensive experience, can you extrapolate three key learnings that those coming to the practice and looking to adopt it quickly will find most useful?

DG: One: Don’t be surprised if your mind seems out of control. That just means you are noticing how much the mind wanders; you’re paying attention inward. Congratulations. Two: Don’t expect to see concrete benefits right away. The payoffs come gradually and subtly. But be assured the best research shows that early on people become less reactive to stress and better able to focus, and the longer you persist in a daily practice session, the better the benefits. Three: Don’t expect that you’ll feel blissful every time you meditate. It’s like going to the gym; you work out no matter how you feel about it. The benefits come from the fact you practice regularly. The point is not to feel any particular way while you do it.

PRH: Who are some of the thought leaders in meditation practicing in the United States today that those very interested in the subject and practice should know about?

DG: I recommend Jon Kabat-Zinn, Joseph Goldstein, and Jack Kornfield. Also Mingyur Rinpoche, Tsoknyi Rinpoche, Phakchok Rinpoche and Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche, all Tibetan teachers I have worked with personally.

PRH: In your book, you state: “We were intrigued by the possibility of some biological pathway where repeated practice led to a steady embodiment of highly positive traits like kindness, patience, presence, and ease under any circumstances. Meditation, we argued, was a tool to foster precisely such beneficial fixtures of being.” I suppose then that it’s never too early to think about incorporating mindfulness into human biology. With that, is there a right way to go about instilling mindfulness in children?

DG: Think of mindfulness as a workout in a mental gym, one that helps children be more focused on what matters, learn better, and stay more calm.

PRH: What is the biggest, most common mistake you see made by those new to meditation? And on the flip side, what is the single most important thing someone new to the practice should do?

DG: Most common mistake: trying too hard. Or giving up. Most important thing to do: keep at it.