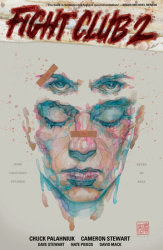

Who is Tyler Durden, really? That was the question at the heart of Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 bestseller Fight Club. The final pages offered what seemed to be an answer, but Twenty years later, Palahniuk’s new graphic novel Fight Club 2 suggests we may have never known Tyler Durden at all. Or, at least, not in the way we thought we did.

What happens when a character escapes an author’s grasp? Why does Palahniuk relate to The Jungle author Upton Sinclair? How is Tyler Durden like a child star? These questions and more are answered in the following interview.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: How did this come together? Why a graphic novel rather than a traditional novel?

CHUCK PALAHNIUK: It came together on kind of a blind date. The thriller writer, Chelsea Kane, who subsequently became one of the characters in the graphic novel, threw a dinner party and she invited Brian Michael Bendis and his wife, and Matt Fraction, and Kelly Sue DeConnick, and then the group of them proceeded to beat up on me, and impress on me that I should write a graphic novel. They promised to teach me the entire form and support me, and I couldn’t say no at that point. They promised to make it so easy, and that’s how it happened.

PRH: Have you considered that this might have been an intervention and not just a dinner party? An ambush, maybe?

CP: I hadn’t thought of that way! If nothing else, maybe they were trying to intervene in my compulsive novel-writing—get me out of rut!

PRH: It seems like to me that you’re ready to put Tyler Durden to bed, but it’s impossible now, isn’t it? I got that impression reading the book, but I might be wrong.

CP: Oh, no. There’s the saying the student only succeeds when he kills the teacher—when you surpass your teacher. While I might claim to want to resolve Tyler, I really wanted Tyler to surpass me.

PRH: That’s really part of the book. I don’t want to give anything away, but Tyler has escaped your grasp and has become something else entirely.

CP: Well, we do seem set up for the next one.

PRH: Oh, there’s going to be a next one?

CP: Well, there’s a baby on the way…

PRH: There’s a line repeated in the book about a child wanting to take on his old man. Do you sometimes feel that way with Tyler? That you’ve got a father-son relationship that’s never going to resolve?

CP: Yeah, but at the same time, that relationship is my meal ticket so I can’t really bitch about it too much!

PRH: It’s like having a child that turns out to be a movie star—a child star.

CP: Yeah! I might bitch and moan, but…

PRH: Sebastian and Marla are married parents living in suburbia. It struck me that a lot of the people who originally picked up the book and then saw the movie are now middle aged people living in suburbia. To what extent is Fight Club 2 a retort to that original audience, or a message?

CP: I never think about the audience, because it’s not my job to fix anyone. The last thing I want in my books is any kind of social engineering or lecture. It was kind of my way of owning up that I was growing older and that my life had become really suburban and that I needed to face the situation from the older side—from my dad’s side—that I couldn’t just be the complaining child for the rest of my life. At some point I had to address the situation from the side of the father and how easy it is to fail at being a father.

PRH: You don’t like to do social engineering and give messages to people, but Tyler does: Tyler does exactly that.

CP: Right. Well, they’re not the most politically correct messages but put them in Tyler’s mouth and that’s fine.

PRH: The original Fight Club was published in the pre-social media era. How do you think it would be received were it published now?

CP: You know, it’s hard to think whether it would do better because it might build its audience faster, or if it would do worse because it might attract criticism faster. It’s hard to say.

PRH: What’s it like when you see people co-opt the book or the graphic novel in ways that are antithetical to their message? I know there’s a scene in the graphic novel where you mention a “Write Club” and all of these other clubs that have popped up, and people getting tattoos and things like that.

CP: It makes me feel like Upton Sinclair when he set out to write The Jungle and he wanted to point out the hardships of immigrant laborers. This was supposed to be the American Communist Manifesto but when people read it, all they took away was that their meat and cheese were full of dirt. He was just infuriated. I don’t feel infuriated, but I can identify with Upton Sinclair.

PRH: I met people who thought it would be really cool to have a Fight Club after they saw the movie. To me it seemed like they might have never been socked in the mouth a couple of times.

CP: I don’t mind the fact that it created a kind of model where people could come together and have consensual experience, because so many people nowadays avoid conflict so much that they don’t really have any freedom around it. They’ve never experienced it. At least this provides a way of experiencing conflict. Otherwise, they’re not having any kind of direct sense of it in the world. There are so few stories that have a social model for men. I think that women’s writing is very, very good at presenting social models, so you’ve got things like The Joy Luck Club and The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, and Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, and How to Make an American Quilt. They’re all presenting models in which women come together and talk about their experiences. With men, those social model narratives are really rare, and few and far between. The only ones I can think of are the “Dead Poet’s Society” where a bunch of kids go into a cave and read poetry, and Fight Club. I think they’re both very similar, but I think Fight Club is a little more honest and realistic than going into a cave and reading poetry and finding enlightenment.

PRH: You’ve mentioned consensual violence. That’s referenced in the graphic novel with “Rize or Die”: that there’s violence in these war zones that can become a sense of play. Could you elaborate on that?

CP: It was kind of a stretch. I wouldn’t say it’s the case that the violence that takes place in a war zone is consensual, but the way that the media handles it as just more content is what I was trying to point out. The media flattens all of this conflict and these dramatic events and just turns it into content to put between commercials and sell things. To the media, conflict has no sort of special importance other than something to put between things. I think that was more of the point I was trying to make. I wouldn’t be surprised though if a lot of conflict wasn’t stage managed by people we’re not aware of—people who pit people against one another and it’s more of a game than a genuine struggle. That wouldn’t surprise me.

PRH: What did you find freeing about the graphic novel? Was there anything that you found restrictive?

CP: The most freeing thing is the fact that the pacing, the transitions, are handled so easily through panels. You have a panel, a panel, a panel, and they lead like a sequence in the film, and you can cut from one thing to a totally different thing and not lose your reader. In long-form prose, you need so many wordy transitions to cut from one thing to the next thing. So many of my novels and my short stories are about creating one device, like a chorus, and using that as a touchstone that allows me to transition instantly to a very different topic. In Fight Club it was the rules: You throw a rule in, and on the other side of the rule there’s a whole different scene, so I was able to write Fight Club like I was editing a film. The panels in comics made presenting the information very easy, but the tough part in comics was suggesting motion with still images, and also setting up a page-turn reveal every two pages. Every two pages I had to have a really strong set-up and then a really strong pay-off as soon as that page was turned, and that requires plotting that is so intense that I don’t think a lot of novelists could do it: in each issue to have 12 to 15 really strong set-ups and pay-offs would be too much for most people and most writers.

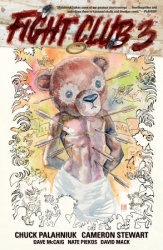

MORE ABOUT FIGHT CLUB 2:

Some imaginary friends never go away . . .

Ten years after starting Project Mayhem, he lives a mundane life. A kid, a wife. Pills to keep his destiny at bay. But it won’t last long, the wife has seen to that. He’s back where he started, but this go-round he’s got more at stake than his own life. The time has arrived . . .Rize or Die.

New York Times bestselling novelist Chuck Palahniuk and acclaimed artist Cameron Stewart have collaborated for one of the most highly anticipated comic book and literary events of 2015–the return of Tyler Durden. The first rule of Fight Club 2 might be not to talk about it, but Fight Club 2 is generating international headlines and will introduce a new generation of readers to Project Mayhem.