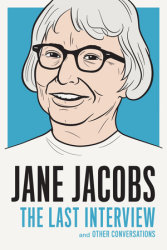

Shortly after the 1961 publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the most famous work of Jane Jacobs, Mademoiselle magazine wrote an article on the enthusiastic response the book was receiving from “people who feel that our cities are being dehumanized.” In the half-century since, American cities have continued to face threats of dehumanization: from heavy-handed city planners, who sought to isolate the chaos of cities into silos of use crisscrossed by highways, to later-day economic pressures that have had a similar homogenizing effect.

As a writer, activist, and seemingly indefatigable celebrant of cities, Jane Jacobs put forth ideas that have continued to remain a remarkable touchstone for those concerned with the forces that impersonalize city life. These forces threaten the “intricate sidewalk ballet” fostered by diverse, human-scale spaces largely left to their own devices, threats identified by Jacobs while peering out the Greenwich Village apartment she settled into after moving to New York from her birthplace in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

To discuss Jacobs’s importance and legacy on her 100th birthday this week, I called up Sharon Zukin, a sociologist at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, who’s brought forth her own equally keen observations of cities in her work and books, including Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change and Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE:Who was Jane Jacobs and what was she writing about in her book Death and Life of Great American Cities?

SHARON ZUKIN: Jacobs was a really remarkable woman and a superlative writer who became more celebrated with each passing year. She managed to be an everywoman, not only of her time, but also of the next few generations. The Death and Life of Great American Cities has got to be one of Random House’s best books ever, not only as a best seller, but also as a book written from the heart that has become a living text for many, many people around the world. Jacobs wrote about the aesthetics and the feeling of a livable city. This is a livable city mostly in the physical terms. Jacobs’s prescription, boiled down to one word, is variety, the variety that people have created in cities. But not everyone appreciated it in her time and not everyone appreciates it now. Jacobs was a contrarian, who was writing in praise of the messiness of big cities in contrast to the mass flight of her generation from cities to suburbs.

PRH:Tell me more about what you mean that she was an “everywoman.”

SZ: I mean both “every” and “woman.” First, over twenty or thirty years, it became obvious that Jacobs expressed the ideas of, not everybody, but many ordinary people and what they value in an urban environment. She also was a woman. She was derided as a “mother” by Robert Moses and to some degree as a woman by academic critics who were males at the time. But she was one of a number of women who wrote books that were so revolutionary and so clear-eyed and so prophetic that they inspired social movements even to our time.

I am thinking here of Jacobs being in the same group as Rachel Carson and Betty Friedan, each one tearing off the veil that covered people’s eyes about the poisoning of the environment by toxic chemicals in Carson’s case and the poisoning of people’s lives by sexism and patriarchy is Friedan’s case. So there were at the very least these three incredible women who wrote these books that became mythical texts of great power. The books were written so that anybody could understand them and they expressed the anguish of ordinary people living in an intolerable world. I don’t know of any other period of time when books written by women were so revolutionary and eventually so influential and, of course, so pilloried.

PRH:So Moses’s criticism was that she was a mother and therefore shouldn’t be writing books?

SZ: I believe he called her a mother who didn’t know anything about urban planning. This was when she and her neighbors protested against three of his plans to tear down parts of lower Manhattan.

One of those plans was to extend Fifth Avenue across Washington Square Park, which would have divided the park into two halves, separated by a busy street.

Another of his plans was to build public housing in the West Village, near where Jacobs lived. And when we say public housing, we mean to demolish existing small houses and maybe warehouses and to replace them with tall towers surrounded by greenspace.

And the third plan was to build the Lower Manhattan Expressway, linking Long Island to the Holland Tunnel, where Broome Street is, which would have caused demolition of a large number of buildings in SoHo.

So Jacobs and the people who were politically active were a thorn in Moses’s flesh. A lot of the opposition that was expressed to extending Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park was expressed by mothers who were bringing their children to play in the park, so I think that was what caused Moses to scoff at Jacobs and the other protesters and to call them “mothers.” That was not short for some obscene or vile term, just that they were “mothers.” And I think probably the more professional architectural critics, who were all male at the time, I think they just thought Jacobs was a woman and for that reason, not someone to be listened to.

PRH:Why do you think the book became so famous? You certainly see it referenced all the time now, despite being over fifty years old.

SZ: Well, if I knew the secret, I would write that kind of book myself. The short answer is, I don’t really know. The longer answer is that I think it took time for Jacobs’s work to seep into the minds of a more radical generation of urban planners and I think her ideas probably were popularized by urban planners and gradually seeped into the mind of architecture or design media writers. I discovered Jacobs work some fifteen or twenty years after she had published Death and Life and already it was appreciated, but I don’t think it was celebrated outside of a small network of urban planning and urban design people.

Despite the sales of the book, and its being quoted widely, and it being celebrated widely, I’m not sure how broad that widespread readership is. I have to say that there are people who are either writers who sell a lot of books, like Edward Glaeser at Harvard who has written about cities, and Amanda Burden, who was the commissioner of city planning in the Bloomberg Administration, who openly declare themselves acolytes of Jane Jacobs, but in practice they absolutely do not adopt all of her views. Burden said, oh yes, I am absolutely an apostle of Jane Jacobs, but supported these hundreds of rezonings that were carried out during the Bloomberg Administration which allowed permanent tall buildings on the big streets, but kept the small-scale side streets, which in my view just increases property values both ways. And Glazer declares her ideas terrific, but he also argues in favor of building taller buildings. It is true that he and Jacobs meet in their mutual dislike of rules and regulations, particularly government rules. So many people pick and choose what they like in Jacobs work or maybe some of her ideas can be interpreted in many different ways, which of course adds to their popularity.

PRH:What do you think Jacobs would say about the New York of today?

SZ: I think she would say it is too homogenous in the direction of affluent neighborhoods. I think she would deplore the demise of individually-owned and family-owned small businesses. The sort of streetscape that she loved was a streetscape that depended on first- and second-generation immigrant storeowners and those are the people who are being priced out of today’s retail spaces. So I think she would deplore a lot of the upscaling of New York today. She was not an opponent of all tall buildings. Again, she praised variety, she praised a juxtaposition of tall buildings and short buildings, old building and new buildings, commercial buildings and theaters and houses, so I think she would like the physical variety that is being zoned into the streetscape in New York. I think she would applaud the very slow moving effort to rebuild the public-housing projects by inserting market-rent apartments in separate buildings and inserting stores, which were explicitly rejected by the New York City Housing Authority when the first public housing projects were planned in the 1930s.