PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: The world of professional ballet holds so much mystery and intrigue and glamour. What was it about the subject specifically that brought you to it as a topic for your newest novel, Astonish Me?

MAGGIE SHIPSTEAD: I’m fascinated by the practices of artists of all kinds and the relationships they have with their own talents and limitations. Since I spend a lot of time writing, and writing is solitary and rooted in the mind and best done while stationary, I find dancers especially exotic and interesting. Their work is dynamic, performative, incredibly demanding on the body. Their careers are relatively brief and can be cut catastrophically short by injury. It’s a vulnerable way to live, and that precariousness – the fact that dancers’ bodies might fail them, no matter how committed they are and how hard they work – seemed to me to have a lot of dramatic potential. And I was also interested in the intimacy of collaboration among dancers: how they have to trust and rely on one another not only to make a good performance but also to stay physically safe and also how attractions and relationships inevitably form among all these young, beautiful people who spend all day touching and sweating and acting out passionate emotions.

PRH: Given all of the fabulously dramatic true stories that have, well, pirouetted from within the world of ballet – Suzanne Farrell’s Holding Onto the Air, Balanchine’s Dancing Cowboy, and most recently Jenifer Ringer’s Dancing Through It and Misty Copeland’s Life in Motion – was there one story from the history of ballet memoir and biography you found particularly inspiring?

MS: Mikhail Baryshnikov’s defection in Toronto in 1974 most directly inspired the course of events in Astonish Me. The Soviets had a sense Baryshnikov was a defection risk and wouldn’t let him tour with the Kirov, but then for some reason he was allowed to go to Canada with a little second-rate troupe that was called the “Bolshoi” but wasn’t. On the night of the last performance, he ran out the back door of a theater and into a waiting getaway car. I used a similar scenario for the defection of my character Arslan Rusakov, partly because I knew it had worked in real life and partly because it gave Joan a role to play in a very dramatic moment and partly because Rusakov, in some ways, is supposed to resemble not Baryshnikov the actual person (whom I purposely didn’t research beyond what I already knew) but the idea of him.

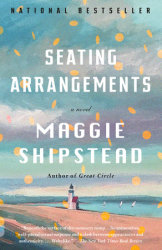

PRH: Following the success of your debut, Seating Arrangements, how did it feel to dive into writing a second novel?

MS: Astonish Me was actually an accident! I’d written a short story about a ballerina that didn’t really work, and when I went to revise, it started to grow and grow. At the time, I was planning to write a different novel for my second book, and this ballet project felt like something on the side that wasn’t really work but I was just playing around with for my own amusement. My first draft was only ninety pages long, but by the time I finished it, I’d started to think it could be its own book. I think I wrote two more drafts in the space of four or five months, and then my editor at Knopf ended up buying the book about two weeks before Seating Arrangements was published. So I was spared having to deal with a lot of the anxiety and self-consciousness and pressure that seems to burden most writers when they sit down to start second books. I didn’t have a brain full of all the things that had happened to or been said about my first book. Maybe that’ll happen with the third one instead. I hope not.

PRH: During your extensive research of the world of ballet while writing Astonish Me, what was the one thing that surprised you most?

MS: When I started watching lots of videos of rehearsals and company classes I was struck by how obscure and inscrutable most of the instructions given to dancers by balletmasters or choreographers or directors seemed to me. As a very verbal person, I’m always trying to articulate exactly what I want or think, but dance is so tied up in the body that words are often an inefficient means of communication. So, for example, in critiquing a dancer, a choreographer might say something like, “Yes, but more like this” (and loosely suggest an arm movement) “and then la LA la la la” (and sing part of the score) “but don’t rush, and then more like – ” (and demonstrate a step). Watching, I don’t remotely understand the nuance of what’s being conveyed, but the dancers usually seem to. They just nod and do it again. Dance really has its own language.

PRH: Any thoughts on what your next project will be?

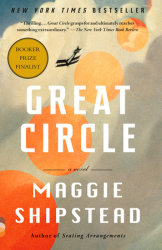

MS: I have a bunch of unfinished short stories I’d really like to stick a fork in, and I’ve been working on a novel about a female pilot trying to fly around the world north-south after World War II.