Essays

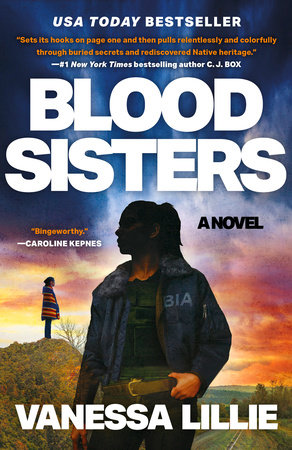

Vanessa Lillie on the True Stories Behind Blood Sisters

Learn about the economic and land injustices for indigenous communities as well as the inspiration behind her riveting thriller.

Vanessa Lillie is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and the author of the bestselling suspense novels Little Voices and For the Best. Vanessa hosts a weekly Instagram Live event with crime fiction authors and was a columnist for the Providence Journal. Her mystery, Blood Sisters, follows a Cherokee archeologist for the Bureau of Indian Affairs who is summoned to rural Oklahoma to investigate the disappearance of two women … one of them her sister.

When I’m writing, the epigraph is like the North Star, a reminder of the direction I’m heading. For my new suspense novel, Blood Sisters, one conversation set that opening line in stone. While on the phone receiving notes on a draft, Osage author and friend, Chelsea T. Hicks, asked if I had ever heard someone say, what happens to the land, happens to the women.

I remember holding my breath after she said it, hearing the heart of my novel spoken aloud. I found the phrase in different forms, often used by Indigenous leaders. A way to help people understand that we are in a relationship with the land, not just an extraction of resources.

While Blood Sisters is fiction, I returned to Northeastern Oklahoma, the land where I was raised, to incorporate as much truth as possible on those pages. Most of the story is set in Picher, Oklahoma, where sixty years of unrestricted lead and zinc mining meant this tiny corner of the state would become the world’s largest source of lead and zinc. After that designation went bust along with the mining companies, the EPA declared Picher one of the most toxic places in the United States.

What happens to the land, happens to the children.

Rebecca Jim is an environmental leader and lifelong advocate for the land, water, and people of Oklahoma. She was also my Native student counselor and wrote my recommendation to get into college. In 2019, I participated in one of Rebecca’s “Toxic Tours,” where she takes folks around to different rivers and creeks in Picher to raise awareness. There are no fish on this tour. Any grasses that grow along the water are stained reddish-orange, similar to the kind I grew up next to.

That day, two men in a pick-up truck slowed down to where we were standing on a dirt road. Rebecca waved and walked over to them. I heard her ask, “How’s she doing?” The man’s young daughter was already on kidney dialysis. In our small town nearby, there are four dialysis centers.

Statistics show that 34% of the children in Picher suffered from lead poisoning, which can produce impaired neurological development that results in lifelong problems. You heard about it in the classrooms, the disproportionally high number of learning disabilities, and the hyperactivity. The issues are at every stage; the miscarriage rate for women in the area is 24%, compared to a national average of 10%.

What happens to the land, happens to the men.

What was ripped out of the earth supplied half the bullets used for World War I. Growing up, I saw black and white photos of men with dusty faces in mining hats, standing in giant rock caverns. Both my great-grandfathers worked in the Picher mines, and both died of Silica, a lung disease similar to black lung.

What happens to the land, happens to the women.

The year I graduated high school, in a trailer home one town over, two people were murdered and two girls who had been celebrating a sixteenth birthday went missing. The need to find the girls as quickly as possible was ignored by local authorities.

It’s believed the girls’ bodies were dumped in Picher. A place where the land is riddled with cavernous mineshafts full of poisonous water. A place that’s uninhabitable now, except for bodies left there to never be found.

Decades passed, and to say the families searched is an understatement. They’ve moved heaven and earth, peered into hell itself making deals with men accused, to get answers. To bring their girls home. I’ve followed the case since it happened in 1999, and my outrage and emotions watching the family search amid injustices, from the dangers of the land to the inept authorities, inspired the crime at the heart of Blood Sisters.

How we treat the land also speaks to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirit crisis. To the disproportionate rate of violence among Native women. To the economic and land injustice suffered by the Quapaw tribe that held the original Picher land leases that were stolen once it became profitable.

There is no question: what happens to the land, happens to all of us.

As an archeologist for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Syd Walker spends her days in Rhode Island trying to protect the land’s indigenous past, even as she’s escaping her own. While Syd is dedicated to her job, she’s haunted by a night of violence she barely escaped in her Oklahoma hometown fifteen years ago. Though she swore she’d never go back, the past comes calling. When a skull is found near the crime scene of her youth, just as her sister, Emma Lou, vanishes, Syd knows she must return home. The deeper Syd digs, the more she uncovers about a string of missing indigenous women cases going back decades. To save her sister, she must expose a darkness in the town that no one wants to face — not even Syd.