Features

The Lost Art of Sentence Diagramming

Every now and then, my Facebook friends will have a nostalgia moment and post a cultural artifact from our cohort’s past. One television staple from the 1970s that we remember with affection was the educational videos that were shown as commercial breaks during Saturday morning cartoons. “Schoolhouse Rock” debuted in January 1973 on ABC. The first season was devoted to teaching children the basics of mathematics. The second season, which started in September of that year, took on the challenges of grammar, focusing much of its attention to the parsing of sentences. I admit that when I encounter certain words for parts of speech, I still hear the lyrics. And when I am copy editing, those song lyrics have actually helped me do my job. For example, “Interjections show excitement or emotion and are generally set apart from a sentence by an exclamation point, or by a comma when the feeling’s not as strong,” and “Conjunction junction: what’s your function? Hooking up words and phrases and clauses,” both set to memorable tunes, have saved me from bone-head errors. (Though not all, as my editors can affirm.) When “Constitution Rock” debuted two years later, it helped me to succeed in seventh-grade social studies. I still remember that the test asked us to write the words to the Preamble; I heard nearly everyone in class singing the song as we wrote the words.

I mention how valuable these learning tools were because another of my favorite ways of approaching language has been turned into a creative work of art. Call Me Ishmael is a collection of postcards that illustrate the opening lines from great works of literature through sentence diagrams. I loved those days in class that we spent diagramming sentences. They impressed on your memory how the different parts of speech operated in sentence construction.

Sentence diagramming is a means by which a sentence is parsed and represented by a structure of lines that establish the relationship among the words in the sentence. Perhaps the best way to envision it is as a “map” of a sentence. In 1847, Stephen Watkins Clark published a book in which he showed a sentence map as a series of bubbles. His rendering looked inelegant, and in 1877, Reid and Kellogg changed the bubbles to a series of lines. The Reid-Kellogg system was adopted by school districts across the country and for decades afterward, schoolchildren were drilled on parts of speech through the construction of diagrams.

To demonstrate how to diagram sentences, consider the following examples. (For further information on sentence diagramming, see these directions.)

The beginning of a diagram is the straight line.

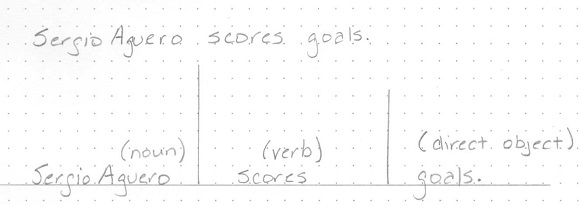

The first objective is to establish the subject and the predicate, that is, who is doing the action and the action being performed. Draw a line between the noun and the verb, as I have done with this simple sentence comprising a noun and a verb.

Sergio Agüero scores.

On the left subject side is “Sergio Agüero.” On the right is “scores.”

The verb, to score, can act as an intransitive verb that needs no object to which to do the action, or it can function as a transitive verb, where the verb takes an object to which the action is done.

So, if we change the sentence to “Sergio Agüero scores goals,” it can be diagrammed with the straight line, with a second vertical line placed after the verb. The direct object is on the same line as the noun and the verb.

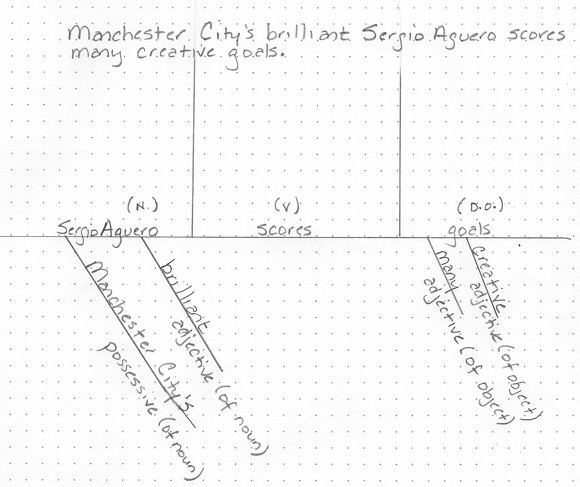

Diagrams become more complicated with the addition of words that modify other words in the sentence. Adjectives modify nouns, so in order to indicate an adjective that is modifying the subject, draw a diagonal line and write the adjective(s) on the diagonal line(s).

Possessives act like adjectives and are indicated in the same way. On the predicate side, if adjectives are used to describe the direct object, draw diagonal lines to indicate those adjectives below that part of the diagram.

Manchester City’s brilliant Sergio Agüero scores many creative goals.

Here, “Manchester City” is the possessive. “Brilliant” is the adjective. And “goals” is the direct object of the verb, which itself is described by the two adjectives “many” and “creative.”

When constructing sentences with direct objects, the item to which the action is being done may itself be affected by whether another person is also interacting with the object. For example, “You may give a gift to your friend,” in which “gift” is the direct object that is being given to “friend,” which functions as the indirect object. Thus the verb “to give” takes both a direct object and an indirect object. The indirect object would be shown on a sentence diagram by a diagonal line coming off the verb.

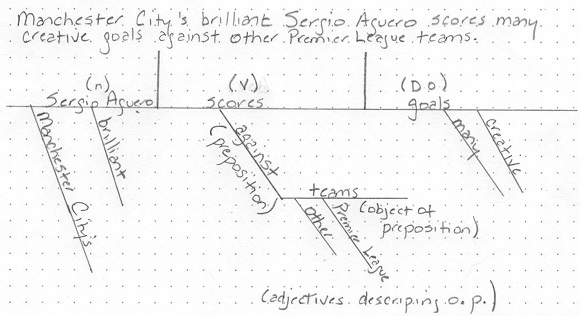

Sometimes, rather than an indirect object, however, that action may be further modified through the use of a preposition. It is a modification of the verb. For example, in modifying this sentence, observe what the preposition is doing:

Manchester City’s brilliant Sergio Agüero scores many creative goals against other Premier League teams.

Here, the preposition “against” modifies the verb by indicating that the action is done to something, but it has an impact on the verb through what is called the “prepositional phrase.”

To indicate a prepositional phrase, write a diagonal line off the verb with the word “against” on it. The object of the prepositional phrase is “teams,” and the adjectives that describe teams are the adjectives “Premier League” and “other.”

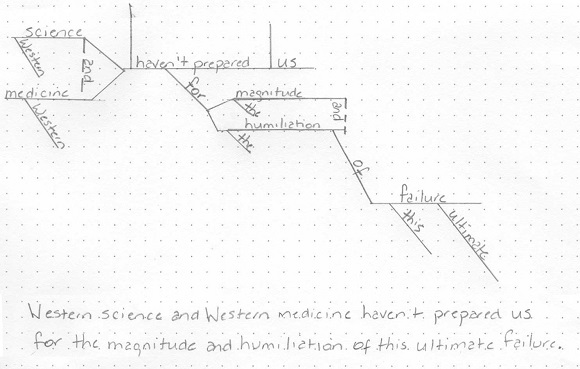

Sentences can also contain more than one subject, or there can be more than one verb. I looked to literature for an example of a more complex sentence, one that I must admit took me a while to break down so that I understood how each word was functioning within this sentence from P.D. James’s The Children of Men.

Western science and Western medicine haven’t prepared us for the magnitude and humiliation of this ultimate failure.

Here there are two subjects — Western science and Western medicine — and two objects of prepositions, which themselves have a prepositional phrase that modifies them. Consider this diagram of the way I parsed James’ sentence.

To diagram this sentence, I used a dotted line to indicate the conjunction — “and” — that connects the two nouns. The verb is followed by a direct object. The prepositional phrase that begins with the preposition “for,” has a double object of the phrase with “the magnitude and the humiliation.” Again, a dotted line is used to indicate the conjunction. That prepositional phrase is itself modified by the prepositional phrase “of this ultimate failure,” which is diagrammed by drawing a diagonal line off the double object.

Sentences can be further complicated with the addition of subordinate clauses, independent clauses that are connected with conjunctions or punctuation, or declarative sentences and multiple other examples where some part of the sentence is unspoken. And the more complex the sentence, the more complex and beautiful the diagram that maps the sentence.

It’s why Call Me Ishmael’s collection of postcards, which contain the opening sentences from twenty-four great works of literature, make a great gift for language lovers. The sentences themselves are revered for the beauty of their construction, choice of words, and rhythm created when they are read out loud. Seeing them as multi-layered diagrams becomes another way to appreciate the geniuses behind the words.