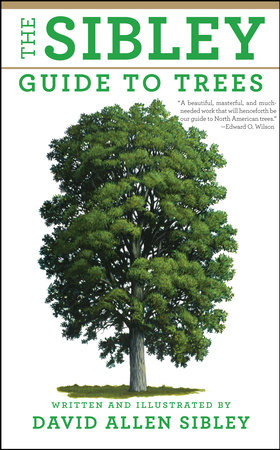

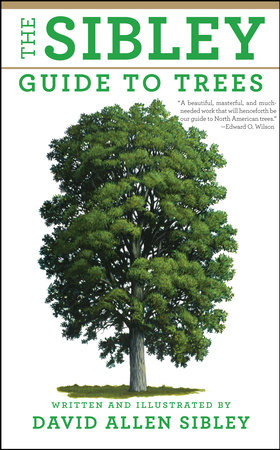

The Sibley Guide to Trees

By David Allen Sibley

By David Allen Sibley

Part of Sibley Guides

Category: Science & Technology

-

$40.00

Sep 15, 2009 | ISBN 9780375415197

Buy the Hardcover:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Illuminated Tarot Coloring Book

The Cloudspotter’s Guide

Splash 13

The Man Who Planted Trees

The Curious World of Bugs

Trees

Collecting Rocks, Gems and Minerals

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics

Camp

Praise

“The Sibley Guide to Trees is so well done that even the most serious birders may find themselves identifying and enjoying trees in their own right . . . All aspects of the trees are shown: leaves (from above and below), buds, flowers, fruits, twigs, and bark. For most species, the autumn leaves are illustrated and, when appropriate, new growth as well . . . The excellent range maps are large and dependable . . . The information is well ordered [and] the guide includes the very latest research . . . The Sibley Guide to Trees will occupy a treasured space right next to The Sibley Guide to Birds . . . It is as monumental and as purely pleasurable as the bird guide, and a masterful and fitting companion.”

—Clay and Pat Sutton, Birding magazine

“A beautiful, masterful, and much-needed work that will henceforth be our guide to the North American trees.”

–Edward O. Wilson

“A wonderful companion volume to David Sibley’s superb bird books, with the same beautifully precise species illustrations and concise, clear descriptions and range maps–altogether an invaluable contribution to our nature literature.”

–Peter Matthiessen, author of Shadow Country

“Unlike birds–the subject of David Sibley’s previous guide–trees of the same species can be different colors at different times of year, different sizes in different places, and even different shapes and sizes in the same place. I thought, therefore, that trees were so replete with variables that a field guide would be impossible. I hadn’ t counted on Sibley’s genius with words and paint to turn the impossible into this brilliant, eminently useful, reality.”

–Richard Ellis, author of Tuna: A Love Story

“I am delighted that the very talented David Sibley has ‘branched out’ to include trees. His illustrations are ideal, and the fact that he chooses to give more examples and variations than other guides will make this a very useful handbook.”

–Robert Bateman, author of Birds

“I think that I shall never see another guide that makes it so easy to identify a tree . . . David Allen Sibley, the preeminent bird-guide author and illustrator, has written a book that is monumental in scope but user-friendly in practical use. Simply put, this is the single most comprehensive guide to North American trees . . . This is an important, new contribution that is certain to help us better understand our natural world.”

—Larry Cox, Tucson Citizen

“David Allen Sibley has done it again. Nine years after the publication of his acclaimed The Sibley Guide to Birds, the book that changed the way we look at our field guides, he’s turned his attention to the second most beloved member of the birder’s world—the tree. In more than 4,000 exquisite paintings, Sibley reveals what to look for to identify 668 native and commonly cultivated trees . . . and to do so the same way you identify birds: from a distance.”

—Matt Mendenhall, Birder’s World

“Sibley’s book brings the advantages of painting to tree identification, keeping plant parts in scale when necessary, showing variations in the shapes of everything from leaves to acorns, and making finely nuanced color choices that really help you parse similar species and outright hybrids . . . It’s obviously made for field use. The durable, flexible cover has end flaps to bookmark whatever you happen to be studying, and the extra size gives you pictures you can see easily . . . This book will become a classic.”

—Jim McCausland, Sunset Magazine

“David Allen Sibley is the artist and author responsible for several excellent bird books (mine are well thumbed), and his tree guide holds its own against the Audubon series. His paintings manage the neat trick of being both evocative and accurate; the telling details are clearly articulated.”

—Dominique Browning, The New York Times Book Review

“Sibley’s inclusiveness for most tree families is remarkable for a one-volume work . . . With a few exceptions . . . the user of this guide can expect to find any native tree found in North America north of Mexico.”

—Alan Pistorius, Northern Woodlands magazine

“[A] blockbuster . . . The book is arranged in taxonomic order. Pines, firs and spruces are at the front of the book with the flowering and nut-bearing trees following. This ordering puts all the pines together, the oaks in one group, the ashes together and so forth. I favor that arrangement in field guides because it demonstrates the natural relationship between families of trees, thus teaching a little botany as well as providing identifications.”

—Paul G. Wiegman, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

“Rich with identification aids (including leaves, nuts, flowers, bark, shape, and range maps), Sibley’s guide will make a useful and entertaining companion . . .”

—Jay Strafford, Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Thousands of paintings featuring well chosen details will help you identify trees even in winter . . . With native trees the most vulnerable and important plants endangered by climate change, we need to sharpen our awareness of wild trees of the woodlands which provide oxygen, food, shelter and erosion control for our ecosystem and which are very different from the cloned exotic trees we plant in our backyard gardens as pampered pets..”

—Carol Stocker, The Boston Globe (#1 on her list of the year’s 10 best garden books)

“The Sibley Guide to Trees, a wealth of knowledge on tree identification, is crafted in Sibley’s aesthetic and easy-to-understand style . . . Fantastic . . . A great new book.”

—Katrina Marland, American Forests magazine

“Is The Sibley Guide to Trees as awesome as The Sibley Guide to Birds? I’d have to say yes. [It] is truly a tree tour de force, a worthy companion to the author’s banner bird guide. One first notices how gorgeous this volume is; the graphic design is subtle but sharp . . . Likely the best amateur tree ID guide on the market. Yet the significance of this work far exceeds its utility. This Sibley Guide serves as a bridge from that other Sibley Guide to the rest of the natural universe . . . The Sibley Guide to Trees is an essential reference text for anyone and everyone who has ever wondered about the identity of a tree. I rank this book right up there with my beloved Sibley Guide to Birds as mandatory editions in any home library.”

—Mike Bergin, 10000birds.com

“Sibley’s guide deserves a place in all libraries, public or private . . . The Sibley Guide to Tree is the closest thing we’ve got to a registry of trees in North America.”

—Chris Watson, Santa Cruz Sentinel

“Invaluable”

—The Hartford Courant

“Is David Allen Sibley’s new work as useful, reliable and interesting as his book on birds? For me, a nonbotanist who has wandered through forests in much of the country, it is. This guidebook is filled with clear, concise descriptions and wonderful drawings of species ranging from sumac to saguaro.”

—John R. Alden, The Plain Dealer

“A treasure trove of knowledge on North American trees. Each page is a wealth of information . . . The beautifully illustrated pages are in color and full detail, down to giving the dimensions and shapes of the acorns from each variety of oak.”

—Sandy Mahaffey, The Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, VA)

“A masterful contribution to the genre . . . With each entry, there’s a short written description of the tree and its main characteristics, along with drawings of the leaves, buds, bark, flowers, fruits and seeds—and in many cases, the tree structure or form. And wow, when you flip through the pine section, you can easily see the difference in the needles and cones. Best of all, Sibley includes a map with each entry showing the natural range of the tree throughout the US and Canada . . . It’s small enough to take with you outside when you want to know whether you’re looking at a white, a black, or a red oak. My copy is likely going to . . . be completely dog-eared within a year or two.”

—Jane Berger, Garden Design Online

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In